The last known self-portrait drawing of Stanley Spencer — executed a few months before his death in 1959 — has been acquired by the gallery dedicated to his work in his hometown, Cookham, Berkshire. The work, which has been purchased with the support of Art Fund on behalf of the Stanley Spencer Gallery, as well as The Band Trust, V&A Purchase Grant Fund and The Friends of Stanley Spencer Gallery, was conceived as a work in its own right before he painted a version in oil, now owned by Tate Britain (pictured above).

The drawing will be showcased as part of the Stanley Spencer Gallery’s current exhibition, LOVE, ART, LOSS: The Wives of Stanley Spencer at the Stanley Spencer Gallery (until Autumn 2021), which explores the relationship between arguably two of the most important figures in the artist’s life —his two wives, Hilda Carline and Patricia Preece (for more information, see Notes to Editors).

Says a spokesperson for the Stanley Spencer Gallery: ‘This is a very important addition to the Stanley Spencer Gallery, and we are grateful to the generous financial support of the Art Fund on behalf of the Stanley Spencer Gallery, as well as The Band Trust, a V&A Purchase Grant Fund and The Friends of Stanley Spencer Gallery.’

Jenny Waldman, Director, Art Fund, said: ‘Spencer’s striking self-portrait offers a unique perspective into the final months of this important British painter. We are delighted to support the Stanley Spencer Gallery in this acquisition, ensuring the work goes on public display in Cookham where the artist was born and found such inspiration.’

The oil painting was commissioned by two friends of the artist, Joy Smith with her husband, and is the ultimate expression of the Spencer’s talent in that it not only a true likeness, but also hints at the uneasy dialectics which must have been at the forefront of a dying man’s mind.

Spencer drew the self-portrait in red conte while observing himself in a dressing table mirror. Conté is a harder, waxier medium than pastel, which creates a finer impression more suitable for portraits. The artist’s gaunt, weathered face is overwhelmed by the frame of his glasses. Yet the deep wrinkles of the forehead, the sagging flesh of his neck, and the grim, sloping downturn of the mouth are offset by a determination and strength found in the unflinching gaze of his right eye (his left eye squints as he searches for a clear image of himself in the mirror), and the resolute set of his eyebrows.

It is an intense, unnerving image, its immediacy of line expressing the frailty of the sitter. It is unmistakably Spencer, with the sharp fringe running across his forehead, a style he wore all his life. The artist has used loose, parallel hatching in the background in order to project the image towards the viewer, but on the face itself, he has created depth and contrast with tight cross-hatching, as he was taught to do at the Slade School of Fine Art in the manner of Michelangelo.

Spencer had a close relationship with the Smith family, who owned the self-portrait. He frequently visited their home in Yorkshire, and later executed an oil painting of Joy along with additional portrait sketches of Joy’s two sons and her husband. Their relationship, and the eventual realisation of the portrait, is charted in a comprehensive document written by the Smiths’ daughter, Catherine, based on correspondence with Spencer, notes left by Joy, contributions from Spencer’s daughters and the writer’s own recollections.

In a letter dated 16th February 1959, we hear the first mention of the possibility of Spencer executing a self-portrait: ‘I know I have promised it but it may never be done all the same. When I went into hospital, I realised that I must do only the work that I wished to do’. When Spencer’s cancer went into remission, he embarked on what would be his last visit to Yorkshire. On 8th July, he met Joy at the Great Northern Hotel and had lunch before taking the train north. He wrote that month: ‘I think late lunch at the Great Northern sounds romantic. I’m all for that, only no hurrying for the train mind.’ Shortly after arrival, he drew the present sketch at Joy’s request.

In the event, Joy Smith was not happy with the resulting image. She apparently — and surprisingly — did not find it a true likeness, but it is more likely that she found it too uncomfortable. Days later, she and Spencer went to Leeds where he bought canvas and oils to paint another version, underdrawn in red conté, which is now owned by Tate, London, but originally hung in the dining room until 1982 when the house was sold. It is certainly a tamer, diluted and easier image with which to live. The oil medium has subdued the immediacy, vigour and raw emotion of the present sketch in which the weight of mortality bears down upon the sitter.

Only two months after that work was completed, Spencer was in the Canadian Hospital in Taplow, Buckinghamshire, not far from Cookham, where he was born and lived for most of his life. After a short remission he returned to hospital in December, where Joy visited him. According to her notes, they discussed ‘the nature of inspiration and the importance of physical form as a source of inspiration and love’ — a conversation whose essence must surely be found in this self-portrait, at once a triumph and a resignation. He died shortly afterwards of cancer aged 68.

The Stanley Spencer exhibtion, which features the drawing, has proved a huge succees. ‘Since re-opening on the 15th August, we are very pleased to report that we have had a nearly normal number of visitors for the time of year,’ says a spokesman. ‘Many of our visitors have said how pleased they are that we have re-opened when so many galleries and museums remain closed or have limited opening times.’

For press information please contact Albany Arts Communications:

Mark Inglefield

mark@albanyartscommunications.com

t: +44 (0) 20 78 79 88 95; m: + 44 (0) 75 84 19 95 00

Michelle Allen

michelle@albanyartscommunications.com

t: +44 (0) 20 78 79 88 95; m: + 44 (0) 79 22 80 72 39

Notes to Editors:

About Stanley Spencer

Sir Stanley Spencer, CBE RA (30 June 1891 – 14 December 1959) attended the Slade School of Art, and is well known for his paintings depicting Biblical scenes occurring in Cookham, the small village beside the River Thames, as well as his large paintings for the Sandham Memorial Chapel and the Shipbuilding on the Clyde series. Spencer’s works often express his fervent if unconventional Christian faith. This is especially evident in the scenes that he based in Cookham. Spencer’s works originally provoked great shock and controversy. Nowadays, they still seem stylistic and experimental, while the nude works foreshadow some of the much later works of Lucian Freud.

About the Stanley Spencer Gallery

The Stanley Spencer Gallery is located in Cookham, Berkshire, and is dedicated to the life and work of Sir Stanley Spencer. Opened in 1962, it is housed within a former Wesleyan Chapel in the High Street, a few minutes’ walk from the house where Spencer was born and where he used to worship. The gallery’s collection comprises over 100 paintings and drawings, and these are exhibited on a regular basis at the gallery, alongside loans from other public and private collections.

On the mezzanine floor level of the gallery is a small study area which houses library and archive material and a computer presentation about the artist and his work. A comprehensive selection of books and articles on Stanley Spencer and related topics is available to be consulted on the premises during opening hours.

The Gallery has won a series of accolades, including its naming as one of the five most ‘unmissable’ small Art Galleries in the UK and the award of a Michelin star in the Great Britain Michelin Green Guide 2014. The Gallery received the Queen’s Award for Voluntary Service in 2016.

Exhibitions have included The Art of Shipbuilding on the Clyde (2011), Stanley Spencer in Cookham (2013 - 2014), Spencer in the Aftermath of the First World War (2014), Paradise Regained (2014), The Creative Genius of Stanley Spencer (2015), Patron Saints: Collecting Stanley Spencer (2018), Friends and Family: Portraits by Stanley (2018- 2019) and Counterpoint: Stanley Spencer and his Contemporaries (2019).

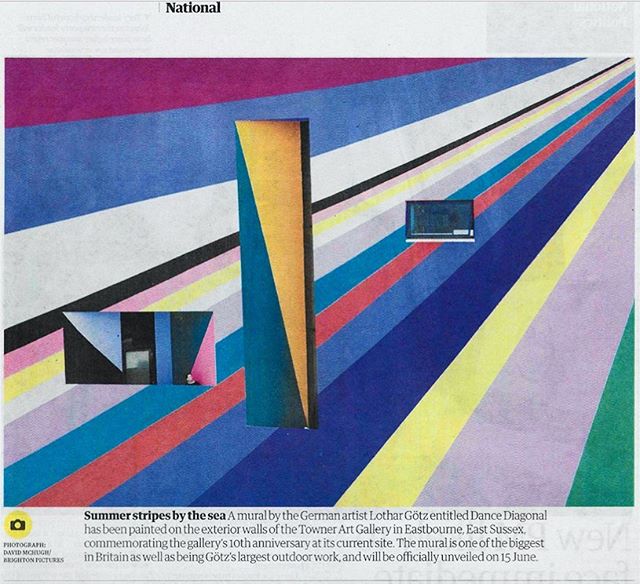

About Art Fund

Art Fund is the national fundraising charity for art. It provides millions of pounds every year to help museums to acquire and share works of art across the UK, further the professional development of their curators, and inspire more people to visit and enjoy their public programmes. In response to Covid-19 Art Fund has made £2 million in adapted funding available to support museums through reopening and beyond, including Respond and Reimagine grants to help meet immediate need and reimagine future ways of working. Art Fund is independently funded, supported by the 159,000 members who buy the National Art Pass, who enjoy free entry to over 240 museums, galleries and historic places, 50% off major exhibitions, and receive Art Quarterly magazine. Art Fund also supports museums through its annual prize, Art Fund Museum of the Year. In a unique edition of the prize for 2020, Art Fund responded to the unprecedented challenges that all museums are facing by selecting five winners and increasing the prize money to £200,000. The winners are Aberdeen Art Gallery; Gairloch Museum; Science Museum; South London Gallery; and Towner Eastbourne. www.artfund.org

About LOVE, ART, LOSS: The Wives of Stanley Spencer

LOVE, ART, LOSS: The Wives of Stanley Spencer, which runs until the autumn 2021, features works drawn from the gallery’s collection, as well as two loans from the Tate, and another from Southampton City Art Gallery, LOVE, ART, LOSS: The Wives of Stanley Spencer seeks to shed light on the effect the two woman had on Spencer’s artistic practice – his unflinching portraits of Preece pre-date by many decades a style adopted by Lucian Freud – while also examining the bizarre love triangle that existed between them.

Spencer was married to Carline when he met Preece in 1929 in Cookham, the Berkshire village where he was born and which was the inspiration for some of his greatest works. Eventually his infatuation led him to divorce Carline and marry Preece, even though she was living with her lover, the artist Dorothy Hepworth, at the time. Preece took Hepworth on their honeymoon and then refused to consummate their marriage, although she continued to live with Hepworth at Spencer’s former marital home in Cookham. The artist then moved to London, living in a bedsit in Swiss Cottage, while having to support not just Carline but Preece, too.

Nevertheless, he continued to paint both women resulting in some of his most powerful work. One of his most famous paintings, Double Nude Portrait: The Artist and his Second Wife (1937), depicts his own and Preece’s body in a frank non-idealised manner, the colours and textures of their flesh are juxtaposed with a raw joint of mutton.

This new direction which led to a series of work he began in 1937 entitled Beatitudes of Love, about ill-matched couples, did not meet with approval from all his supporters. Indeed, it prompted the following response from his early patron, Sir Edward Marsh, ‘Terrible, terrible Stanley!’

This raw portrayal of his personal life and use of hyper-realism was unique amongst Modern British artists at this time. His unabated self-expression was truly avant-garde and his portraits in particular, evoke the conflicting forces at play: love and objectivity, lover and wife, voyeurism and the gaze, the consummated and the unfulfilled.

The works in LOVE, ART, LOSS, which include paintings and rarely seen studies, attest to the complicated but profound relationships he had with both women. While, Preece refused his pleas for a divorce holding out to become Lady Spencer when he was knighted the year of his death in 1959, Spencer’s deep affection for the estranged Carline resumed in the 1940s – during which both suffered from depression – particularly through their letters, which Spencer continued even after her death in 1950.

Comments the show’s curator Amanda Bradley: ‘Spencer had wanted two wives, the spiritual support from Hilda and carefree excitement from Patricia, but effectively ended up with none. Spencer’s aching sense of loss and confusion is evident in his unique evocation of the frailty of human condition that was seminal to the development of Modern British Art, without whom Lucien Freud, Francis Bacon and Grayson Perry would not be as we know them today.’

Stanley Spencer Gallery

High Street, Cookham, Berkshire, SL6 9SJ

t: +44 16 28 53 10 92

info@stanleyspencer.org.uk

www.stanleyspencer.org.uk

Exhibition Opening Times

5 Nov ’20 to 31 March ’21

Thurs – Sun only

11.00am – 4.30pm

Open Boxing Day & New Year’s Day

Also open Mon 28th to Wed 30th Dec

Closed Xmas Eve & Xmas Day

Admission charge: £6.00

Concessions (over 60, Students): £4.50

Carers, Under 16 (with adult): FREE

Instagram: @StanleySpencerGallery

Facebook: @StanleySpencerGallery

Twitter: @SpencerCookham

Download full press release below